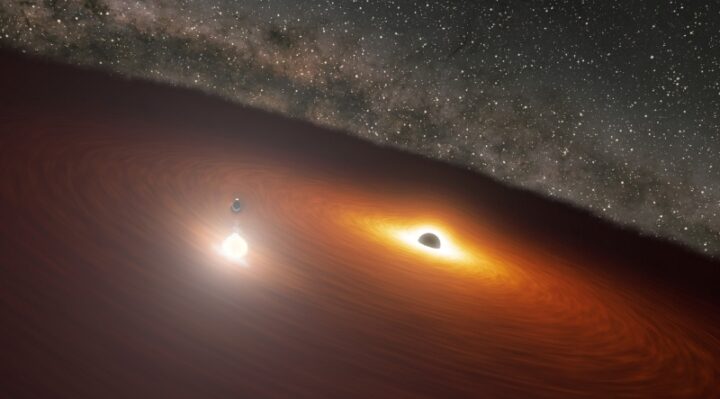

Astronomers have detected dancing supermassive black holes because of bright lights detected by NASA telescopes

Two powerful telescopes have recently detected the closest pair of supermassive black holes ever observed, located just 300 light-years apart. These black holes, residing in the center of colliding galaxies known as MCG-03-34-64, were spotted through different wavelengths using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. Although black holes themselves cannot be seen, these two stand out due to the intense light emitted as gas and dust surrounding them are drawn in and heated up. These active galactic nuclei, as they are called, release jets of material and winds that shape the galaxies they inhabit.

This particular pair of black holes is the closest ever observed through both visible and X-ray light. While black hole pairs have been detected before, they are typically much farther apart. Astronomers stumbled upon this discovery when Hubble revealed three bright diffraction spikes in the glowing gas of the MCG-03-34-64 galaxy. These diffraction spikes appear when light bends around the telescope’s mirror. Intrigued, the research team, led by Anna Trindade Falcão from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, decided to investigate further.

Using Chandra’s X-ray data, the scientists identified two powerful X-ray sources corresponding to the optical light observed by Hubble. This evidence strongly suggested the presence of two closely spaced supermassive black holes. To confirm their findings, the team also examined archival radio wave data from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico, which supported their conclusion that these black holes were emitting energetic radio waves as well.

While two black holes were identified, the origin of the third diffraction spike seen by Hubble remains a mystery. It could be gas illuminated by energy from one of the black holes, but more data is needed for confirmation.

Though black hole pairs closer than these have been detected through radio telescopes, this is the first time such a pair has been observed in multiple wavelengths of light. Once the central forces of their galaxies, these black holes are now on a collision course due to a galactic merger. In about 100 million years, their spiral will culminate in a merger, releasing gravitational waves that could potentially be detected by the future LISA mission, a European Space Agency project slated for the 2030s.